One of the most salient features of our culture today is that there is so much slop. Each of us has been subjected to this; each of us contributes their share. But what even is AI slop?

To investigate this, I:

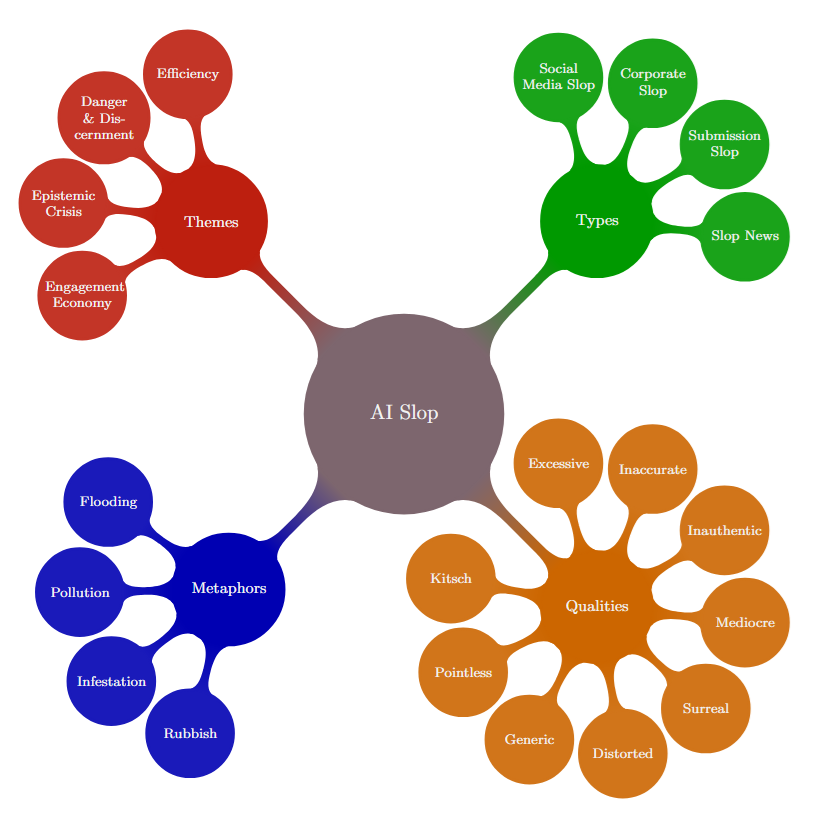

- Conducted qualitative and quantitative analyses of sources referenced in the Wikipedia page on AI slop. From these, I construct four dimensions for slop: themes, types, qualities, and metaphors.

- Created the SlopNews dataset, used to analyse the statistical features of slop content. Compared to non-slop news, slop news is less complex, less varied, and has more positive sentiment.

- Created an archive (slopscooper) where I collect examples and publications about AI slop.

This is a synthesized version of my Master's dissertation. To read the whole thing, click here.

This is the first post of a series on AI slop. It goes into the contextual information and theoretical aspects (history, philosophy, media theory) of slop. The second part presents the results of the study on what people say about slop. The third part analyses the quantitative aspects slop itself.

Introduction

The Oxford Word of the Year 2024 was brain rot; their shortlist included demure, dynamic pricing, lore, romantasy, and slop. They define slop as:

(n.) Art, writing, or other content generated using artificial intelligence, shared and distributed online in an indiscriminate or intrusive way, and characterized as being of low quality, inauthentic, or inaccurate.

Although the word slop was used to refer to low-quality writing as far back as the 19th century, coinage of its current AI-related usage has been attributed to Simon Willison. According to Aleksic (2024), two key events are related to its popularisation: the creation of its Wikipedia page and the publication of an article in the New York Times. From its origin in AI and tech internet circles, the term’s usage has seen a remarkable 334% increase in usage in 2024.

While no academic papers on AI slop have been published, there are two related preprints: an unrelated technical advance in AI writing quality and a discussion of AI-generated propaganda, which they call slopaganda. While the scientific literature is sparse, there are numerous op-eds, blog posts and similar media which extensively discuss the subject. The most interesting piece I've read on this is, by far, Drowning in Slop by Max Read.

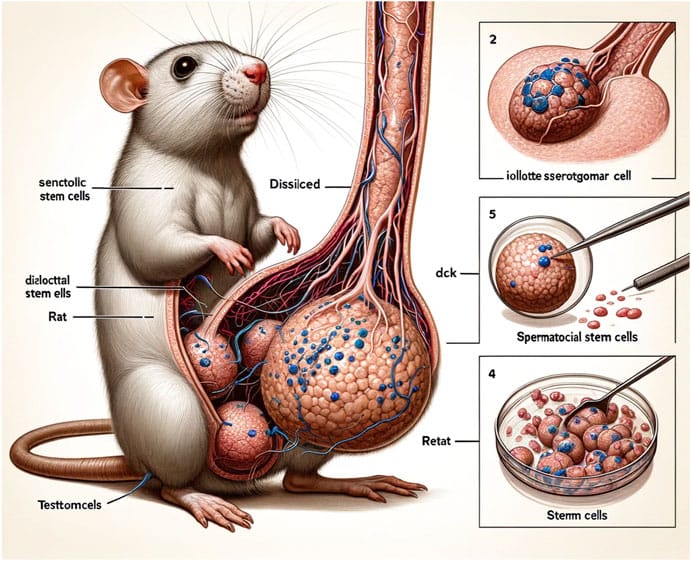

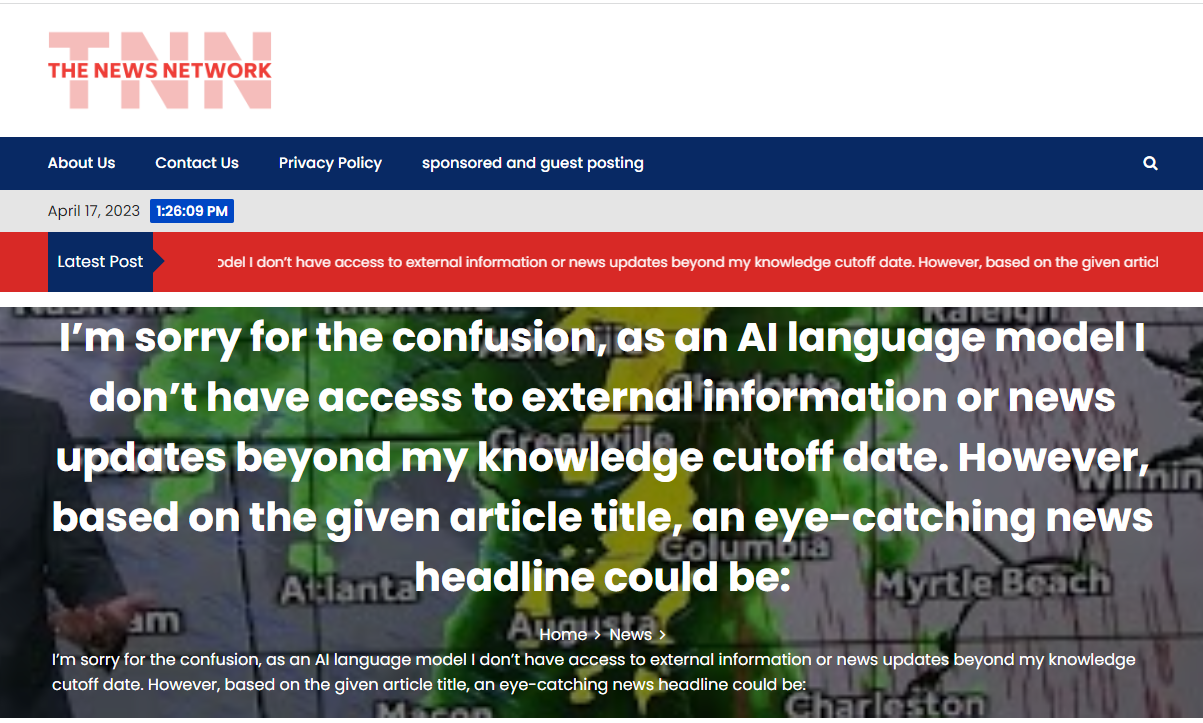

The most conspicuous kind of AI slop is social media slop: surreal AI-generated content spread on Facebook for driving engagement, the most notorious example being Shrimp Jesus. Other examples include fake Amazon product listings, fake summary and biography e-books, misleading AI-generated advice such as eating rocks, and incorrect scientific illustrations such the giant rat penis.

Here are a few visual examples:

As a general phenomenon, slop is not a new: humans have long generated “authentic” meaningless content for profit. Earlier forms include practices such as content farms, paper mills, clickbait, and search engine optimization (SEO) manipulation. However, recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) technology have dramatically lowered the cost and effort required to create slop.

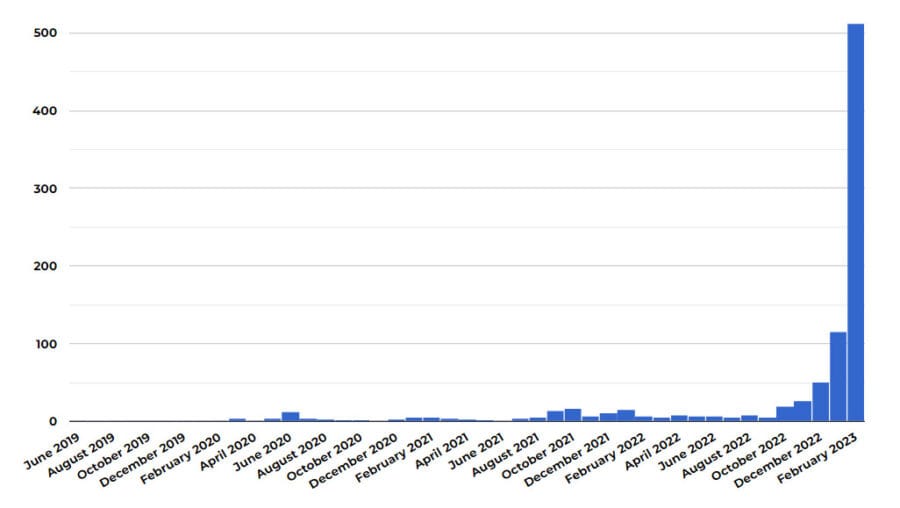

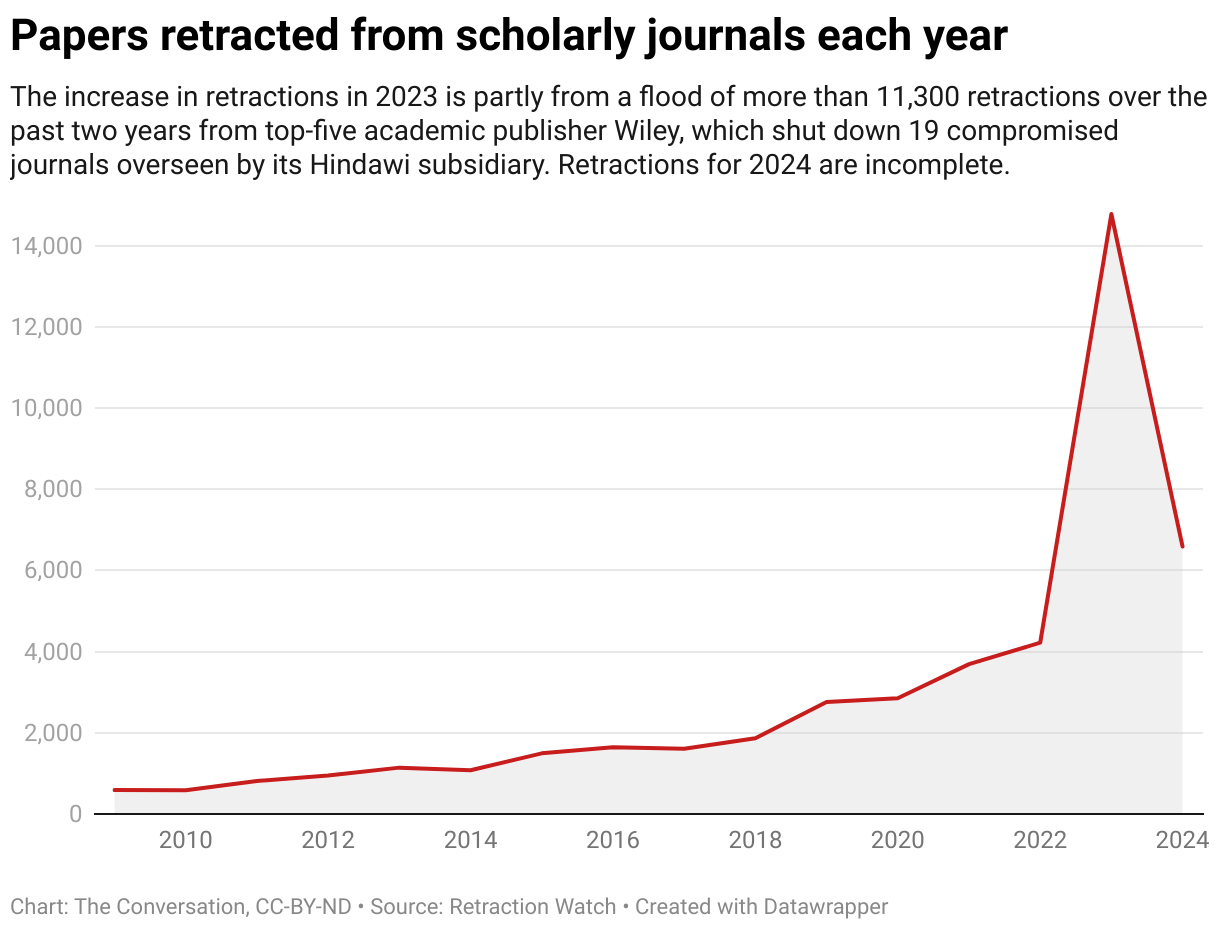

Consequences of this shift are already being felt in systems that rely on good-faith submissions, such as: open source coding projects, job applications, book publishing, library catalogues, and academic papers. Across these domains, organizations are reporting a deluge low-quality synthetic content that they must manage. Sharp increases in low-quality or problematic submissions following the release of ChatGPT in 2022, as can be seen in the following figures:

Slop also impacts systems which incentivise quantity over quality—such as engagement-driven social media and SEO. With increasing pressure to automate and scale content creation, slop has become a structural by-product of platform incentives and algorithmic visibility. Systems where the primary function is signalling effort – such as cover letters, recommendation letters and performance reviews – are expected to face similar disruption (Mollick, 2025).

In theoretical terms, slop is related to ideas of epistemic crisis, information disorder, and enshittification. In practical terms, slop is a pressing issue for the fields of academic integrity, content moderation, and information reliability. By flooding information environments with inauthentic, incoherent, or manipulative content, slop worsens epistemic instability, undermines the utility of digital systems, and places new burdens on already overstretched institutions.

There is increasing concern about misinformation, lack of trust in institutions, mainstreaming of conspiracy theories and erosion of shared reality. This work has convinced me that we have moved on from postmodernism into another era---the slop era.

Related frameworks

Slop is similar to other forms of problematic information:

- Disinformation: false information spread with malicious intent (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017).

- Misinformation: false information spread inadvertently (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017).

- Hallucination: AI-generated content which seems plausible but is factually incorrect (Huang et al., 2025).

- Rumour: information which is unverified; a debunked rumour can be classified as misinformation or disinformation depending on the intent of the source (Zubiaga et al., 2019).

- Fake news: news which is false and public; unlike rumours, they always refer to facts which can be verified (Zubiaga et al., 2019).

- Spam: intrusive messages typically associated with scams.

- Bullshit: communication characterized by indifference to truth (Frankfurt, 2009).

Unlike misinformation and hallucination, slop is not necessarily false. Unlike spam and disinformation, it is not necessarily malicious. Its closest parallels are spam (with its emphasis on quantity) and bullshit (with its emphasis on plausibility). Slop has been likened to a metaphorical “distributed denial-of-service” (DDoS) attack, where an excess of useless requests prevents a system from processing legitimate ones (Purdy, 2025).

Related organizations to this issue include AI detectors (e.g., GPTZero, Originality.ai, Pangram), information reliability/fact-checking (e.g., Full Fact, NewsGuard) and scientific integrity tools (e.g., Problematic Paper Screener, Retraction Watch database).

Since it neither causes physical harm nor is obviously toxic, AI slop does not fit neatly into taxonomies of AI risk. In the MIT AI Risk Taxonomy, constructed from 65 other taxonomies, slop is most closely aligned with "subdomain 3.2: pollution of information ecosystem and loss of consensus reality”. Although this category is primarily concerned with issues like personalization and filter bubbles (also known as echo chambers), it remains the most fitting descriptor for the risks associated with the proliferation of slop.

Another relevant taxonomy was developed by the Center for Security and Emerging Technology. In this framework, we can categorize slop as an intangible issue of detrimental content and/or democratic norms. Intangible refers to phenomena that are difficult to observe or lack a direct material manifestation. Issue denotes an ongoing concern or a possible occurrence rather than a specific event. Slop falls under detrimental content through its association with misinformation, and it relates to democratic norms via its contribution to information disorder.

On slop

AI slop can be understood in the context of the philosophical concept of bullshit: discourse indifferent to its truth-value; instead of prioritizing accuracy, it is created for some other objective, such as plausibility or persuasion (Cohen, 2002; Easwaran, 2023; Frankfurt, 2009). This is distinct from lying, which involves intentionally stating a known falsehood, and thus having an interest in its truth-value.

Instead of “hallucinating”, AI systems can be better understood to be bullshitting – generating plausible-sounding text without regard for truth (Gorrieri, 2024; Hicks et al., 2024; Trevisan et al., 2024). In this sense, generating slop is also bullshitting: communicating something not for its informational value but for its effect (e.g., engagement on social media).

There are other definitions of bullshit. For example, instead of depending on the intentions of the speaker, something can be said to be bullshit if its content are ‘unclarifiable’ (Cohen, 2002). This is the definition most commonly used in psychology, particularly in studies of susceptibility to “pseudoprofound bullshit” (Pennycook et al., 2015).

We should consider, however, the intentions of those who created these definitions:

- the original intent-based definition was created to describe rhetoric in politics and advertising;

- the content-based view was developed to expose obscurity in French Marxism; and

- psychological approaches were created to criticise new-age spirituality.

All of them had an axe to grind and had an adversarial relationship to their subject. This emphasizes the role that normativity and context play in subjective labels such as bullshit and slop.

The psychological study of epistemically suspect beliefs (e.g., bullshit, fake news) draws heavily on the heuristics-and-biases tradition from behavioural economics (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). This body of literature, however, tends to frame bias as the exploitation of vulnerabilities in human rationality (e.g., see Muzumdar et al., 2025; Pennycook & Rand, 2019). In this way, it neglects the performative and emotional dimensions of communication—treating misinformation as a failure in the transmission of information rather than a socially and affectively embedded practice (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017). Similar critiques have already been raised in economics (Infante et al., 2016) and sociology (Barker, 2011).

It's media ↩️

Rather than treating slop as a purely technological or psychological artifact, we can also consider the structural and socioeconomic conditions that incentivize slop production: algorithmic visibility, low-cost scaling, and platform monetization.

There is substantial public anxiety surrounding misinformation (Cellan-Jones, 2017; World Economic Forum, 2024):

- In the United States, adults perceived made-up news as a more pressing issue than violent crime, climate change, racism, illegal immigration, terrorism, or sexism.

- 64% of US citizens believe “fabricated news stories cause a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current issues and events” while

- 51% “cite the public’s ability to distinguish between facts and opinions as a very big problem” (Barthel et al., 2016).

The rise of AI-generated content – which has been shown to be highly persuasive in certain situations (Costello et al., 2025; Koebler, 2025) – risks making this situation worse.

AI slop operates similar to disinformation (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017) in that both consist of repetitive and low-value content. This is remarkably similar to the political strategy articulated by Steve Bannon: “flood the zone with shit” (Illing, 2020). The goal is not to convince, but to exhaust and confuse. While slop does not have these as its main purposes, they happen as consequences of the prevalence of slop in an informational environment.

Ironically, information about misinformation is often misleading. Evidence suggests the problem posed by fake news is overstated. The values cited above reflect the public perception of the issue, not its empirical prevalence.

- The average American’s exposure to fake news has been found to be low, at around 0.15% (Allen et al., 2020).

- A study by the UK Centre for Emerging Technology and Security (CETaS) found no evidence that AI disinformation or deepfakes impacted UK, French or European elections results in 2024 (Stockwell, 2024).

- In most cases, social media actually increases exposure to alternative viewpoints, while only about 8% of the population exist in ideological “echo chambers” (Arguedas et al., 2022).

This reveals that the core danger is not necessarily an information environment “poisoned” with falsehoods, but the pervasive fear and corrosion of public trust that the perception of such an environment creates. Therefore, the goal should not be to simply “neutralize the poison” with technical fixes, but rather to rebuild the perception of trust in the information environment.

Market incentives – from click-driven ad revenue to “publish or perish” academia – fuel the production of slop by motivating agents to create a high volume of low value content (Knibbs, 2024a; Labbé et al., 2025b). In this way, this is not an issue of psychological susceptibility, but of the consequences of the systems with which people are compelled to engage.

Digital platforms play a large role in the dynamics of the epistemic crisis. One interesting concept to understand their functioning is enshittification (Doctorow, 2023). While originally it refers to the process by which platforms compromise the quality of their service, the term is sometimes used as a “general term of abuse” (Frankfurt, 2009), that is, as a strictly derogatory term (not unlike the terms bullshit and slop).

In contexts where plausibility and engagement are prioritized over accuracy and “connection,” the result is what we might call slopification: systematic incentives toward the creation of low-effort and low-quality crap instead of things which are actually worthwhile.

Images are AI slop's most iconic form, as illustrated by Shrimp Jesus and other “weird AI crap” (Read, 2024). It operates at the limits of moderation, as it is not necessarily factually incorrect (like fake news) or offensive (like hate speech). Yet, its informational effects can be understood in the context of “pollution of information ecosystem and loss of consensus reality” (Slattery et al., 2025). By its sheer scale, AI slop reduces the signal-to-noise ratio of the information environment and demands additional effort in order to filter it.

You have now been initiated into slop studies. Keep reading in the second part, where we investigate what people say about AI slop, and use that to create a taxonomy.

If you would like to be notified whenever I release more stuff like this, sign up here.